My full review of Vladimir Pištalo’s novel, Tesla, a Portrait with Masks, a novel, appeared in the Washington Independent Review of Books on February 10th. That review was written to advise the prospective reader. Here, I want–for my own edification and for that of fellow writers–to examine a small, particular aspect of how Pištalo writes. Specifically, I want to take note, very briefly, of the vibrant way in which Pištalo presents setting.

Rather than merely describe buildings or scenery, Pištalo makes his settings come alive through action. Everything is in motion. For example, when describing the World Expo of 1893, he gives us a few sentences of straight description: “The lake mirrored the images of palaces. Gondolas skated across the rippling water. The wind undulated the plumes of the fountains.” (p.217) Even those three sentences are active. But this is followed by sentences such as “…The Maharaja of Kapurthala exhibited his spectacular mustache–the sight of which made twenty women faint. Princess Eulalia of Spain took Harun al-Rashid walks across Chicago and even smoked in public. The Ferris wheel, propelled by sighs, rotated on the largest axle in the world.” (p.217)

But Pištalo’s real sense of motion comes in the next paragraph:

“The masses rolled in through the gates on the Midway. Ladies sweated underneath their corsets. Those sweating ladies had traveled a long way from their boring farms where the howling wind and sputtering oil lamps kept them company. For the first time in their lives, in the World of Light they could see Eastman’s camera, Benz’s automobile, Krupp’s cannons, the zipper, chewing gum, and the electric kitchen. While they sighed wistfully, their children dragged them toward a Venus de Milo sculpted in chocolate. Shrill voices resounded everywhere.

‘Let’s see the lion tamer!’

‘Let’s go to the Lapland and the Algerian villages!’

‘Let’s go to Buffalo Bill’s circus!’

‘Let’s take a balloon ride!’

‘Let’s do it all!'” (p.218)

He gives us the sense of place, of wonder, of excitement by succinctly contrasting the Expo with what visitors have left behind, by listing the wonders they see, and most importantly–by dialogue–the excited demands of the children who want to go off in all directions at once, ending with “Let’s do it all!” The image of ladies entering, sweating under their corsets, gives one a sense of crowds, without actually stating it. “Shrill voices sounded everywhere.”

Pištalo presents the setting of New York in the 1920s:

“The youth of Europe were dead.

‘That’s boring!’

‘Let’s dance!'”

Hair and skirts became two feet shorter. The music of jangled pianos and pouty clarinets rang out. Young people leaped and threw their legs sideways. Beads bounced over women’s breasts…On the silver screen, people split their pants and threw pies at each other in jerky movements. Even the squirrels in Central Park moved in the strobe-like fashion of silent films.” (page 375.)

There is a huge feeling of frenetic motion here that captures the spirit of the ’20s. Contrast that with this passage introducing the 1930s, which–despite the end of prohibition–captures it’s heaviness and its slower pace:

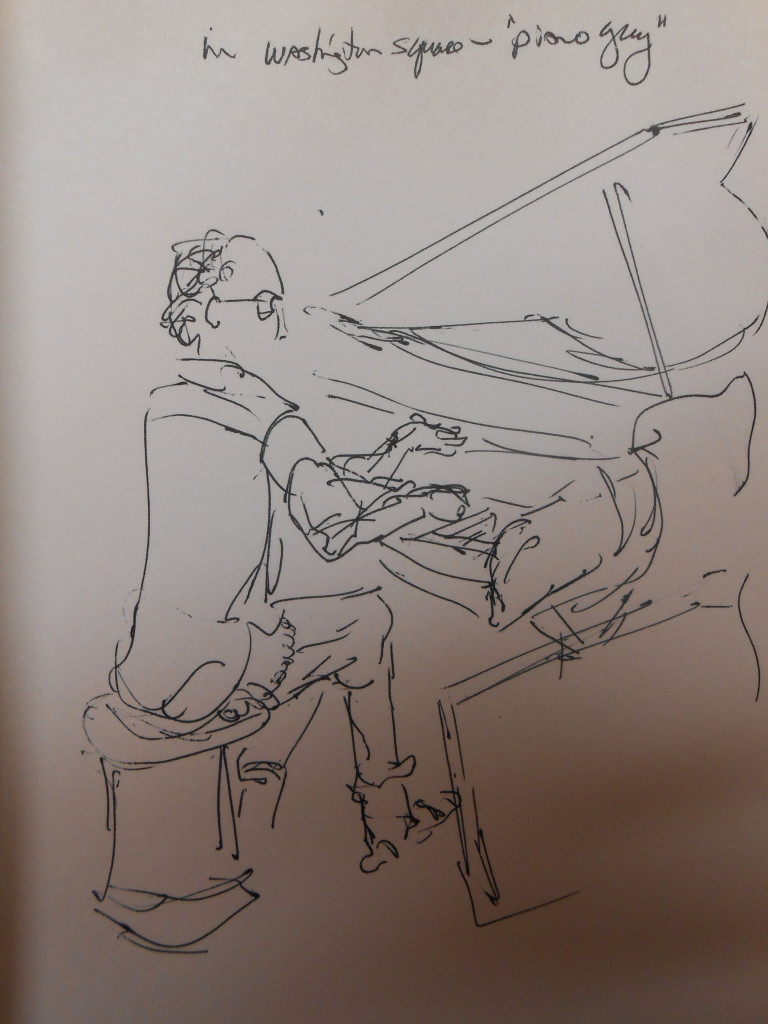

“The lapels of the coats were turned up. Hats pushed against hats on the streets. Prohibition was finally over. ‘No more thirst!” the winners celebrated. Inside quiet bars, martinis and cocktails glowed like yellow and red lamps. Ashtrays brimmed with rouged cigarette butts. Someone played the piano in a sly manner. The sounds dripped…Sappy movies started to idealize the tenements…” (p.408)

There are also two descriptions of scenery, each seen from a moving train, which Pištalo uses to effect. The first, when Tesla is a child on a train from Gospic to Vienna, going off to school with his friend Mojo:

“Nikola and Mojo were glued to the window as they tried to catch the lay of the land.

‘Look at that little house.’

‘The railway guard lives there,’ Mojo explained.

The little house, a horse tied to the fense, and the chickens in the yard flashed by and were replaced by other scenes.

‘It’s really foggy in these parts.’

‘Look at the castle.’

People disembarked at stations…

Hanging pots of geraniums swayed in the breeze in front of station buildings. Railroad men hit the car wheels with long-handled hammers and listened to the clang. Uniformed dispatchers raised their signs to signal the train’s departure. The sound of their whistles pierced the mouse-gray afternoon.” (p.36)

Contrast this with his train trip from New York to Wydencliffe:

“The elevated train rumbled two stories about the ground.

The inquisitive traveler stared at other people’s windows. Like a moth, he peeped into lit-up rooms from the darkness.

In one room, a hairy man with curlers on his chest, soundlessly, shouted into the distorted face of a woman.

In another room, a ballerina hooked her thumbs against her collar bones. A pirouette transformed her into a white smudge.

In a third room, St. Jerome hugged the lion…

Rows of golden windows…

Ah,the rows of golden windows whipped through deserted streets.

When the windows trickled away, Tesla became bored…” (p.345-346)

These have been just a few random notes on Pištalo’s use of action to present setting that might be useful for other writers to try out in their own work..